As someone who has studied career education (CE) in the California Community Colleges (CCC) for many years, I am concerned about the potential impact of proposed cuts to the CCC budget for 2020-21 on the students served by CE programs, and on the state’s workforce—especially at a time when some job sectors might collapse and people will need new skills. The CE mission of the CCC is critical to ensuring that Californians have opportunities to prepare for the many “middle skill” jobs the state’s employers have struggled to fill in recent years—jobs requiring more than a high school education but less than a bachelor’s degree (e.g., technicians in engineering, healthcare, advanced manufacturing).

CE programs are more costly for colleges to offer than other instructional programs, as they are often heavily dependent on expensive equipment, and they require more frequent curricular change as well as structured engagement with the employer community to ensure they remain relevant to workforce needs. In addition, many have class size restrictions due to access to equipment or specialized accreditation requirements.

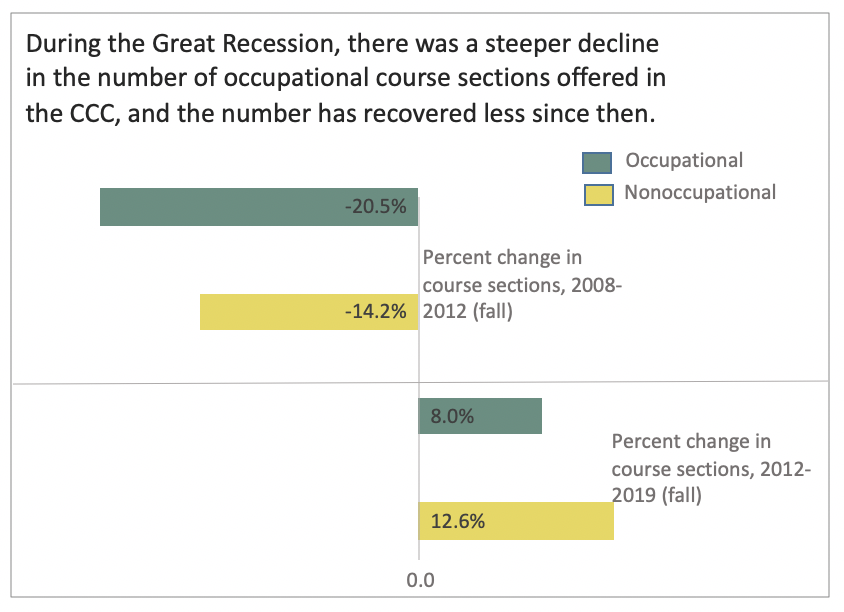

The higher cost of offering CE courses has left them more vulnerable when budgets get tight. After reaching a peak in 2008, the number of course sections offered across the CCC dropped by nearly 17 percent by 2012, as colleges responded to state budget cuts during the Great Recession. Courses defined as “occupational”—those included in course sequences making up CE programs—were cut more substantially, dropping by more than 20 percent compared to a decline of 14 percent for “nonoccupational” courses, as shown in the figure below.[i] Occupational course sections have been reinstated more slowly since 2012, growing by eight percent compared to nearly 13 percent for nonoccupational courses.

Responding at least in part to research and recommendations about the importance of preserving high cost CE programs, state policymakers passed legislation to implement the Strong Workforce Program in 2016. The bill made a number of changes to policy to support the CE mission of community colleges, including increased funding to better account for the higher cost of such programs. Early evidence of the impact is promising. While the overall growth in occupational course sections since the Great Recession is still below that for nonoccupational courses (as shown in the graph above), the pattern is the opposite in the several years since the Strong Workforce Program was passed. The number of occupational course sections offered has increased by three percent since 2016 compared to a slight decline (by 1%) in nonoccupational course offerings. This suggests that the additional funding and other policy changes may be having the intended effect of helping colleges to maintain and even grow their CE programs.

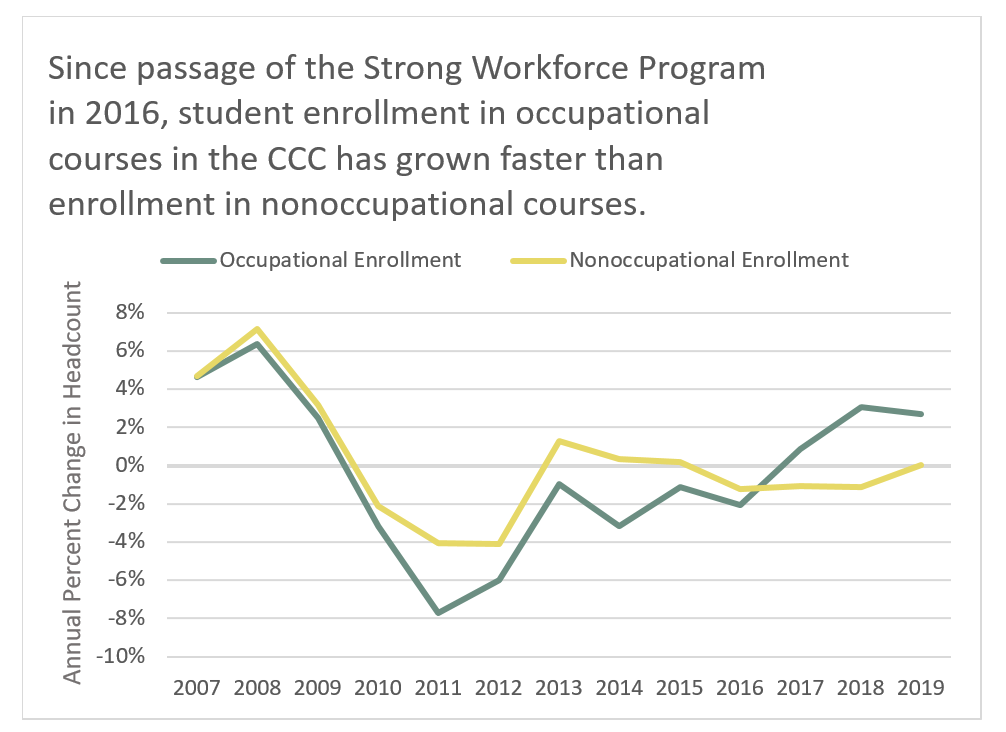

The impact on student enrollment is likewise promising, displayed in the figure below depicting the annual percent change in the number of students enrolled in occupational and nonoccupational courses. Enrollment in occupational courses has grown by an average of two percent per year since the Strong Workforce program was passed in 2016, while it has remained fairly flat in nonoccupational courses.

It is critical for policymakers to keep these patterns in mind as we enter another period of huge state budget deficits. The governor’s revised budget for 2020-21 included significant cuts to the Strong Workforce Program, endangering the availability of CE at a time when it is likely to be in high demand. California is experiencing significant job losses in entertainment, hospitality, and other service sectors that employ more women, young adults, and people of color. Many of these job losses will be prolonged or even permanent, leading displaced workers to the CCC in search of training for jobs in sectors that will be in higher demand, including those requiring the kind of technical skills provided in CE programs. The Legislative Analyst’s Office recently offered alternative options for targeting any cuts to the CCC budget, including an option that focuses on preserving funding for CE.

Without explicit efforts to maintain CE courses and programs, colleges will likely do what they’ve done in past recessions—cut the programs most needed to help displaced workers re-train for better opportunities. The “path of least resistance” for colleges would be to change their mix of courses to focus on less costly general education, especially if students who would otherwise enroll in one of the state’s public universities turn instead to a community college to stay closer to home during a pandemic, and to pay lower tuition for courses that will be largely online. This could increase existing disparities in educational opportunity, as the populations that traditionally rely on the CCC for access to higher education are displaced by more economically advantaged students. Maintaining funding for the Strong Workforce Program could help colleges keep an adequate focus on serving the students most in need at this challenging time.

[i] Based on the CCC’s SAM code classification, using data gathered from the CCC’s Datamart. The figures for occupational course sections include courses that are defined as “clearly” and “advanced” occupational. Courses that are “possibly” occupational and those exclusively enrolling students in apprenticeship programs are excluded, although including them does not change the story.